At first glance, it seems pretty straightforward that the Super Mario Brothers games are a fantasy series. They take place in a fantastic world with dragons, princesses, and magic mushrooms, and the RPGs in the series have all the typical role-playing elements of a fantasy game. But when you look at the entire franchise, particularly the Super Mario Galaxy games, it seems almost certain that the game is science fiction, or at least science fantasy. Here are five reasons revolving around specific titles in the series that prove the Super Mario Brothers are works of science fiction.

Note: I’m defining science fiction broadly as “a genre of fiction dealing with imaginative content such as futuristic settings and technology, space travel, time travel, faster than light travel, parallel universes and extraterrestrial life.”

The Many Worlds of Super Mario Galaxy

Up until the arrival of Nintendo, many game designers had programming backgrounds. The creator of Mario, Shigeru Miyamoto, was unique in having an art background and imbued his games with his artistic sensibility. The original Super Mario Bros. was a visual breakthrough after the pixel blips of the Atari, creating appealing characters, scrolling worlds, and blue skies (most backgrounds were black from fear of causing headaches and eyestrain for gamers). Miyamoto revolutionized the gaming canvas with a simple shift in the palette and more importantly, focused on the aesthetics as much as the gameplay. His attention to character designs like the goombas, Mario himself, and Bowser is a huge part of what has made them so iconic all these decades later. In a world inspired by Alice in Wonderland and filled with enormous mushrooms and fiery castles, he seamlessly integrated the art into the level design.

The Super Mario Galaxy games that came a few decades later for the Wii weren’t just an evolution of that first foray into gaming art. They are probably the most innovative games ever developed. There are other titles that outdo it in terms of visuals, physical scope, and narrative, but none in its creative blending of game mechanics and gorgeous artistry. Galaxy subverted gravity to literally flip gaming on its head. Planetoids, brand new suits (traverse clouds, use drills to power your way through the center of a planet, and sting like a bee), along with labyrinthine levels, help make the universe your sandbox. Mario is the Kirk of the Nintendo Universe, rushing headfirst into adventure. But unlike the crew of the Enterprise, Mario embraces the strange physics of these vibrant worlds, leaping from world to world, interacting with them and changing their very fabric. It’s an amazing sensation navigating a lava world which you then freeze so you can skate across a barren ice lake to reach a new launch star—just one of many acts of terraforming.

It’s during one of these excursions that you come across the Starshine Beach Galaxy. It immediately struck me how much it resembled Isle Delfino, the central location of Super Mario Sunshine (Mario’s outing on the Game Cube), and home to the Piantas, the oddly happy race with palm trees growing out of their heads. Yoshi is there, the tropical climate is back, and all that was missing was my Fludd rocket pack.

On another trip, I visited the Supermassive Galaxy, a world where all the enemies came supersized. Whether it was different laws of gravity, or the chemical composition of the atmosphere, the Goombas, Koopa Troopas, and their surrounding building blocks resembled the gigantic forces in Giant Land from Super Mario Bros. 3 and the Tiny-Huge Island of Super Mario 64 (depending on which approach you took).

That’s when I began to wonder: were the unique worlds of the Super Mario series different galaxies Mario had ventured to? What if all the fantasy worlds of Super Mario were various adventures in the separate galaxies, and the Mushroom Kingdom was just one of many worlds? That is pretty much what is shown in the first Super Mario Galaxy when Princess Peach’s Castle is taken from its foundations by Bowser and lifted up into space above the planet.

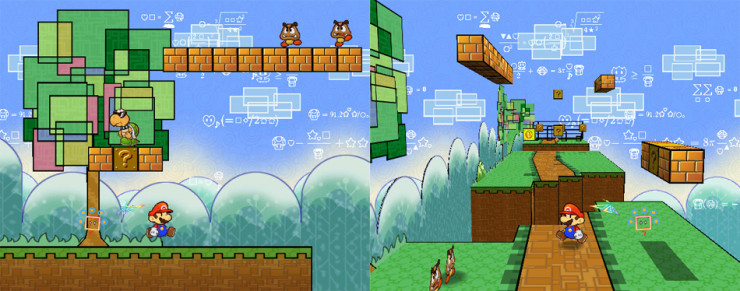

The Dimensional Shifting of Super Paper Mario Wii

The first time I read about and actually understood the science of dimensions and their connection with our own world was in Michio Kaku’s Hyperspace. He postulated the idea of how 2D beings would be flabbergasted by the possibility of 3D existence, unable to comprehend going from a flat plane to the geometric explosion of spatial propulsion. In Super Paper Mario, dimensional shifting becomes the key game mechanic, bridging the NES and SNES classics with their 3D counterparts. Count Bleck is trying to open a singularity called “The Void” in hopes of wiping out the universe. But Mario, with the use of a dimensional shifter, uses quantum mechanics to show that even a paper cut can be deadly in the right hands.

It was probably the best illustration of dimensional limitations I’d experienced, incorporating clever puzzles in every nook and alleyway. See a hole you can’t traverse? Flip into 3D and go around it. An impregnable wall? Change your perspective and suddenly, the way is clear. If superstrings were titillations in higher dimensions, I wondered how my mad waves of the Wii controller and their ululations in my finger muscles were transmuting two dimensions down. Butterflies aren’t the only ones who can cause storms on the other side of the planet.

Mario’s first shifts into 3D involved ripping apart the threads of his flat existence. It caused him pain and damage, sustainable only in short sprints. By the time Mario 64 swings around, he’s become adjusted to the three dimensions, and by the time of Galaxy, he’s prancing across space, flying free.

The Super Mario Bros 2 That Wasn’t Really Super Mario Bros. 2

I’ve talked a lot about physics, and it’s because the original Mario games set the standard by which gaming physics are judged. The original NES platformers had smooth controls that were intuitive and made jumping and running feel right. Try loading up any of the other Nintendo games of the time, and you’ll notice many of them have jumps that feel clunky and frustrating, resulting in a lot of cheap deaths and busted controllers. Super Mario Bros. 3 was probably the pinnacle of the Mario 2D platformers, slightly edging Super Mario World. A huge part of that was the variety of suits that introduced all new mechanics, as well as the steampunk background; huge airships, themed worlds, and Bowser statues that fired laser beams.

Among all the Mario games, one stands out for being vastly different. Super Mario Brothers 2 started out as Doki Doki Panic before morphing into a strange sequel for the original Super Mario Brothers. In the biggest change to the gameplay, the brothers were accompanied by Princess Toadstool and Toad. Their task was to rescue Dreamland from Wart who has been creating a legion of monsters via his dream machine. I always used either Luigi or the Princess, the former because of his long, wiggling jump, and the latter because she could hover. Stomping on enemies no longer crushed them. Instead, you picked them up and hurtled them at each other. The world felt much more whimsical with surreal elements like eagle faced gates, moby dicks spouting water, magic carpets, and cherries leading to invincibility stars. It was a Kafkaesque romp with bizarre enemies and masked fiends. It’s also probably the best argument that the franchise is essentially fantasy.

But the ending renders it moot because after defeating Wart, we find out it was all a part of Mario’s dream. Talk about lucid dreaming.

Time Travel and Other Mad Science

What would it be like to travel through your subconscious meanderings? Jump back in time to see the early stages of the Mushroom Kingdom and fight off an alien invasion with your younger self? Or become microsized and enter Bowser’s body in an uncomfortably intestinal collaboration? The Mario & Luigi series took all that was strange about the Mario series and made it stranger, infusing elements of science fiction and pop culture to give gamers quirks that only magic mushrooms could inspire.

Or a mad professor. Professor Elvin Gadd—an Albert Einstein/Thomas Edison hybrid—invents a time machine in Partners in Time, the Fludd used in Sunshine, as well as the Poltergust 3000 that allows Luigi to vacuum up ghosts in Luigi’s Mansion. Gadd shares the same voice actor for Yoshi, Kazumi Totaka, and both augment the super powers the brothers wield. Likewise, both have their own obscure language that is incomprehensible gibberish unless you’re a baby—so it’s a good thing baby Mario and Luigi are around to help out their future selves battle the alien horde of the Shroob in Partners in Time. It turns out baby tears are the kryptonite to the Shroob, so the Professors Gadd channel baby tears (manufactured, of course) into a hydrogush blaster to save the world and send everyone back to their proper place in the timeline.

All along, I’ve assumed that unlike Link in the Zelda games, Mario is the same Mario throughout the series. Is that even the case? Or does each Mario game represent an alternate history, a new iteration of the mythical plumber? What were plumbers like thousands of years ago? The word plumber has its origins in the Roman word for lead, plumbum. Anyone who worked with piping and baths (many of which were made of lead) were called Plumbarius. Mario and Luigi don’t just represent the common Joe—they embody the highly malleable and adaptable materials that have been the cornerstone of civilization.

That Time the Dinosaurs Didn’t All Go Extinct

On the inverse, the daily life of a goomba isn’t easy. They spend their whole lives training in the ranks of Bowser’s dystopia in order to become fodder for Mario and his goons, crushed to death (if you haven’t, I highly recommend this short film about life from the perspective of a Goomba). The other minions in Koopa’s army don’t fare much better. If only Bowser would give up his master plan to kidnap Princess Peach, what kind of empire could they build?

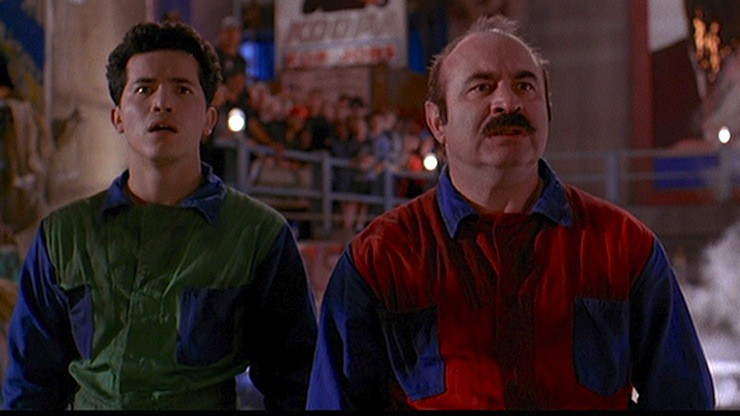

The most maligned entry into the entire Mario franchise has to be the Super Mario Brothers movie, a film that explored an alternate history where the dinosaurs didn’t go extinct and evolved into a race led by a Dennis Hopper rendered Bowser. I was surprised when I recently rewatched the movie and enjoyed it. It wasn’t anywhere near as bad as the reviews had stated, and as Chris Lough wrote in his retrospective for Tor, “There’s only one real problem with the Super Mario Bros. movie: its name.” Even Miyamoto commented: “[In] the end, it was a very fun project that they put a lot of effort into… The one thing that I still have some regrets about is that the movie may have tried to get a little too close to what the Mario Bros. video games were. And in that sense, it became a movie that was about a video game, rather than being an entertaining movie in and of itself.” (italics mine)

I was stunned that Miyamoto’s main problem with the film was that it remained too faithful to the game, rather than veering off in a completely different direction. Some of its creative ways of incorporating elements from the game proved too disturbing for reviewers, including a younger me who found the small-headed lizard faced goombas as well as the realistically raptor-like Yoshi scary when I first saw it. An older me appreciated all that they tried to do, including centering the romance around Luigi and Daisy, the oppressive fascist society propagated by Bowser, and the only aspect that maintained its visual appeal during its migration to the big screen: the bob-ombs. Dino-Manhattan is a dark and terrifying reflection of our own world if it had squandered all its resources. The set designs had that 80s/90s type of appeal that was grungy, futuresque, and real. No backgrounds constructed fully in CG that make everything look fake and too color-corrected. If the Mario Brothers film was an original work of science fiction, it would probably have had a much better reception than it did. But even as a Mario film, I liked Bob Hoskins’ grouchy take on the iconic hero in conjunction with the more optimistic and naive Luigi.

For me, the biggest issue with the Super Mario film is that it went too far into science fiction side of things without bringing along any of the fantasy elements. Super Mario Galaxy towed the line perfectly, and resulted in one of the greatest games ever developed. Other iterations in the series have also walked that tightrope, most to critical acclaim. In the latest iteration of Mario, Super Mario World 3D, they actually went back to straight fantasy (emphasizing the multiplayer), and while the reviews have been mostly positive, it’s been considered a step back, a retread that doesn’t add anything new.

I know Super Mario Brothers probably falls into the science fantasy or space adventure category more than science fiction because even though it meets most of wiki’s definition for SF, it fails in the plausibility category. No one is going to believe the games could ever be real. That’s part of what makes the film so important to my argument because it bridges the gap, staying faithful to the spirit of the games, at least according to Miyamoto, while somewhat maintaining plausibility. I can imagine an alternate universe where dinosaurs evolved and moved on, though they’d more likely be similar to Star Trek: Voyager’s Voth than Bowser.

Independent of which genre the series falls squarely into, my personal preference for the Mario games are the ones that incorporate elements of science fiction.

That is, other than the American Super Mario Brothers 2, which has always had a special place in my heart because it was so different and magical. I’ve always wondered why Nintendo never made a direct sequel in a similar art style with 2D mechanics (although Super Mario World 3D I mentioned above does allow you to play as any of the four characters). It could be a merging of alternate histories where the Mario films took off and resulted in a bunch of sequels that Mario and crew live through, only to wake up and find out it was all a nightmare. The final boss would be the film Mario vs. the video game Mario. Who would win? It wouldn’t matter as Bowser or another enemy would show up and kidnap someone who would need to be rescued, at which point they’d team up or compete against one another and— hopefully, the cycle never ends and the games keep on evolving as Mario and company take on new mythic battles, one stomp at a time.

This article was originally published in June 2015. Let us know where you think Super Mario Odyssey fits on the science fiction-to-fantasy continuum!

Peter Tieryas is a character artist who has worked on films like Guardians of the Galaxy, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs 2, and Alice in Wonderland. His novel, Bald New World, was listed as one of Buzzfeed’s 15 Highly Anticipated Books as well as Publisher Weekly’s Best Science Fiction Books of Summer 2014. His writing has been published in places like Kotaku, Kyoto Journal, Tor.com, Electric Literature, Evergreen Review, and ZYZZYVA, and he tweets @TieryasXu.

I was somewhat amused to learn that Super Mario Bros. 3 is itself a work of fiction within the Mario universe – it’s intended to be a dramatization of some other adventure :)